Recently, a comment that today’s large neural networks may be “slightly conscious” has stirred up the AI corner of twitter. Apart from giving everyone a chance to proclaim their own intuitions about consciousness and its abundance or scarcity in nature, the tweet sadly put a spotlight on the fact that we are still far away from any sort of science-based public discourse on this issue. And while everyone seems to be laughing at the proposition, there is no consensus what exactly is so funny about it.

What does it even mean to be conscious?

The first problem is of course that people mean very different things when they talk about consciousness. What we all should mean is subjective experience, that it feels like something to perceive a scene, to endure pain, or to reflect on the experience itself (Tononi et al., 2016). The capability to perform any kind of function in itself (meaning regardless of any accompanying feeling) is beside the point and should be easily testable in general.

How are we to judge whether anything is conscious?

Testing for subjective experience is tricky business. When it comes to humans, we typically just ask (using more or less sophisticated ways to obtain a report). But already in humans, asking has obvious limitations (someone might be aware, but paralyzed, or might not be able to hear the question). How could we ever judge whether an artificial system is conscious?

One strategy is to identify neuronal correlates of consciousness (NCC) in humans under conditions where we can be (almost) certain about whether or not the person is conscious, or whether or not they consciously experienced something (extrapolating from our own experiences). Close examination of these NCC may then allow us to form hypotheses about general features of conscious systems. For example, there is growing consensus that the complexity of our cortical neuronal activity reliably indicates the presence or absence of consciousness (Sarasso et al., 2021).

Another way to address the issue is to think about the essential properties of subjective experience directly, and to ask what properties a physical system must fulfill in order to be a substrate of consciousness (Ellia et al., 2021). This is the starting point of integrated information theory (IIT).

What we should not do is conflate consciousness with intelligence, judge by intuition (which typically also conflates consciousness with behavior), or make up theories of consciousness divorced from experimental evidence on the neural correlates of consciousness or the properties of subjective experience. Thus, any reply to the “slightly conscious” tweet pointing out the functional limitations of current ANNs without reference to a theory of consciousness is tangential at best.

Can artificial systems be conscious at all?

One issue with the NCC approach is that we do not have and never will have theory-independent empirical evidence about whether any kind of artificial system is conscious or not. If you judge by similarity of behavior, you presuppose input-output functionalism. On the other hand, absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.

In the end, the question whether artificial systems can be conscious or not has to be evaluated based on inference to the best explanation. It’s a matter of reason and argument, not testable in itself, but based on theories that are testable in human beings (with all the inherent caveats). If, for example, it turns out that IIT holds up and we can account for every discernable feature of our experiences based on the causal interaction structure of a particular patch of neurons in the cerebral cortex, what reasons would we have to exclude an artificial neuron-by-neuron copy of this structure from being conscious?

[Even according to IIT, there could still be reasons why this artificial system might not be conscious in the same way as the brain. For example, each artificial neuron could itself be more integrated than the brain, and then we might not find a maximum of integrated information at the level of the interacting artificial neurons by IIT’s exclusion postulate.]

The real issue is that most of today’s artificial neural networks (ANNs) are not organized in the same way as neurons in the human brain. The brain is massively interconnected. Even the primary visual cortex receives many more back connections from other cortical regions than feedforward connections from the retina and LGN (Muckli & Petro, 2013). The human brain also still has many more connections and neurons than today’s large neural networks. But, of course, there are also creatures with as few as ~300 neurons (C. Elegans). Is C. Elegans slightly conscious?

Does it make sense for anything to be “slightly conscious”?

In healthy human beings, consciousness seems rather binary: either the light is on, or it is off. However, in patients with damage to smaller or larger parts of the cerebral cortex it seems reasonable to talk about degrees of consciousness. A graded notion of consciousness also makes intuitive sense across species. In IIT, there is a quantity (\(\Phi\)) corresponding to the level of consciousness of a maximally integrated system that forms a physical substrate of consciousness. Nevertheless, there is some debate about the question (Bayne et al. 2016).

What should be less controversial is that the contents of consciousness may range over different modalities and may differ in scope for different organisms/systems. Different cortical substructures seem to give rise to different aspects within our experience, and localized lesions can lead to the loss of specific conscious contents. In this way, we can conceive of a slightly conscious being, which might lack emotions, a sense of smell, or touch, abstract concepts, pain and pleasure, etc., but still have all the necessary and sufficient properties for being conscious.

Does network size matter?

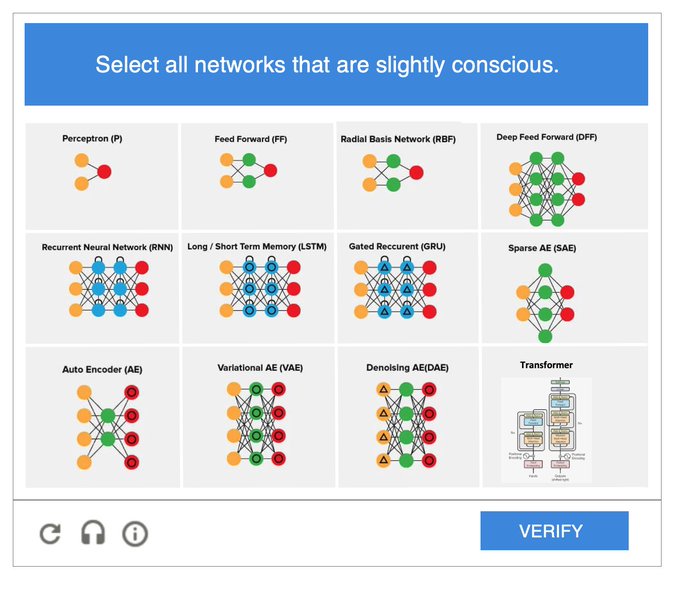

When it comes to complex systems, more may be different (Anderson, 1972). In other words, quantitative changes may under certain circumstances lead to qualitative ones. For example, relative size seems to matter for the ability of ANNs to learn robustly (Bubeck & Sellke, 2021). On the other hand, large ANNs are not really doing anything qualitatively different from small ones. If a small ANN capable of simple image recognition is not conscious, a large ANN of the same type capable of more sophisticated image recognition on a larger data set is not going to be conscious either. What distinguishes different types of networks is their internal structure, no matter the size. That’s the premise of Melanie Mitchell’s hilarious “Captcha” counter to the “slightly conscious” tweet (see image below).

Network Captcha. Image credit: Melanie Mitchell.

Intended or not, this tweet is pretty deep. It plays on all the questions raised above and highlights an issue which has been called the “small network argument” by Herzog et al. (2007), who showed that many theories of consciousness imply that small networks with fewer than ten neurons can, in principle, be conscious. This holds for all current computational and causal structure theories, including global workspace theory, higher order thought theories, and IIT (Doerig et al., 2020). Once a theory defines necessary and sufficient criteria for consciousness, it is possible to construct a small system that fulfills the respective characteristics. In other words, any theory of consciousness will give you a minimal network that is “slightly conscious” and that won’t fit with our intuitions about consciousness.

The only way to avoid the issue is by postulating additional, arbitrary requirements (such as a minimal size or complexity). However, this would be unscientific, because, again, we do not have independent evidence about whether these small systems are conscious or not. Larger networks may have a larger capacity for consciousness. However, consciousness doesn’t just jump into being once the network processes X amount of information or forms a particular network structure constituted of Y amounts of neurons. A theory of consciousness should be able to answer Mitchell’s network captcha based on principled reasons. Instead of trying to overcome the “small network” issue, we should embrace it, as done by IIT.

Which network structures support consciousness?

Which of Mitchell’s networks would count as “slightly conscious” according to IIT? First, the networks would have to be physically implemented, not simulated. Next, none of the feed forward architectures qualify, deep or not, because purely feed forward systems have no intrinsic boundaries and cannot form the substrate of a unified experience (Oizumi et al, 2014). The rest might be slightly conscious. Critically, however, it would still feel like not much at all to be such a system. Specific contents require specific substructures.

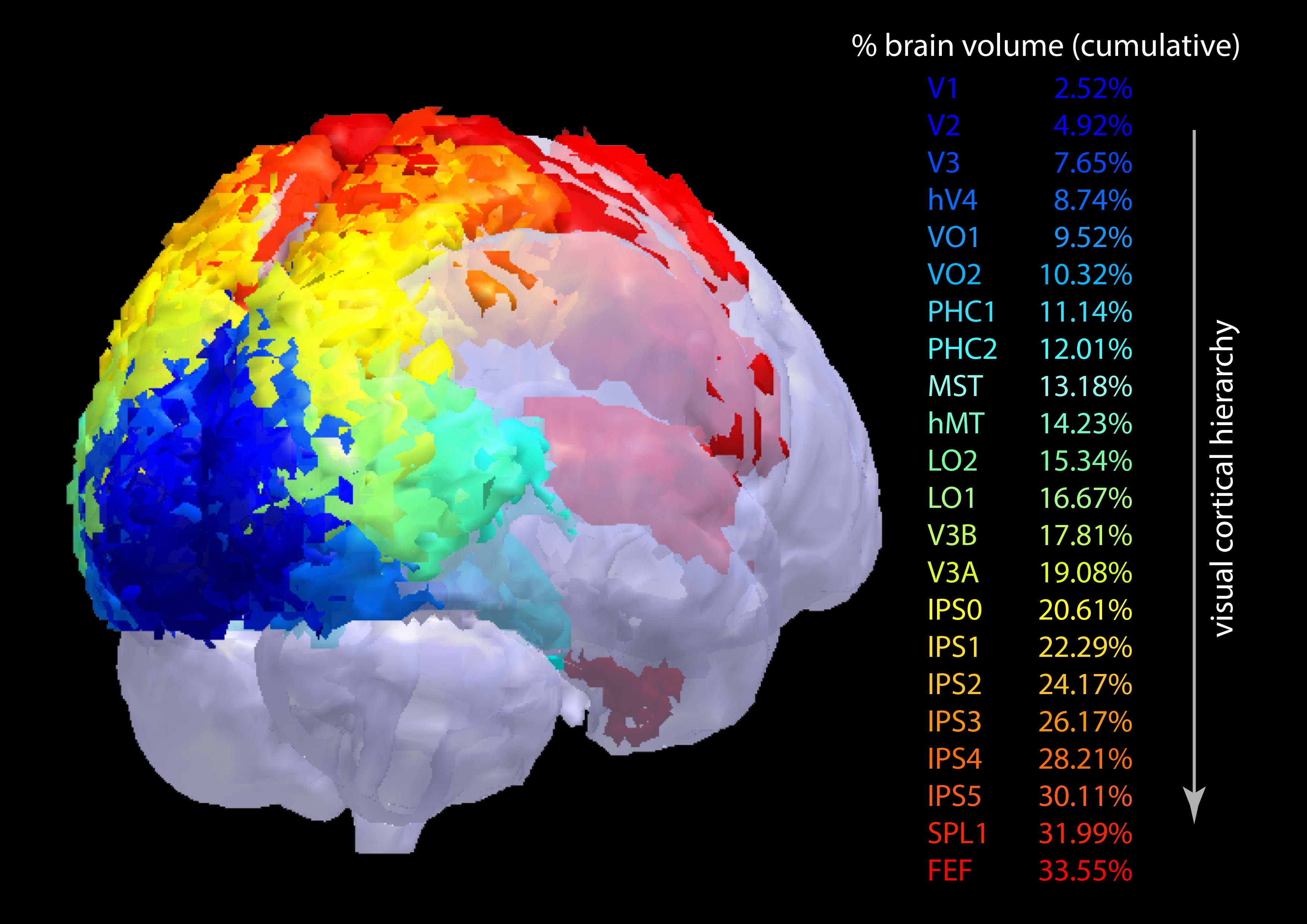

For example, IIT proposes that grid-like network structures may underlie our experience of spatial extendedness (Haun & Tononi, 2019). While grids are simple structures that are easy to describe, a grid-like neural network may give rise to a rich causal structure with many irreducible higher-order interactions. Interconnected stacks or “pyramids” of grids may form the basis for our perceptual experiences: More than a third of our cerebral cortex (at least 38%) is topographically organized as pyramids of grids (see figure below). This includes large portions of the posterior cortex, which is part of the current best anatomical candidate for full and content-specific neural correlates of consciousness in the human brain (Koch et al., 2016).

Topographically organized regions in the brain. Image credit: Chen Song. Based on data by (Wang et al., 2015) and (Sereno & Huang, 2014).

Would a patch of topographically organized neurons in isolation (with the right background conditions) form a slightly conscious system, experiencing spatial extendedness and nothing else? According to IIT, this is a possibility. As pointed out by Cohen and Dennett’s (2011) “perfect experiment”, we cannot test this claim directly. However, there are current efforts to determine whether access or reportability are necessary for consciousness based on not-quite-perfect experiments in combination with inferences to the best explanation (Melloni et al., 2021; see also the preregistration).

Conclusion

Given the progress in AI and also biomedical research, there are difficult questions about the presence or absence of consciousness ahead of us. Due to the experimental challenges inherent to a science of consciousness, we must rely on the results of many different types of experiments, combined with a coherent theory of consciousness that offers a good explanation for the experimental observations. When it comes to today’s large neural networks, all major theories of consciousness would deny them any sort of experience. However, as the small network issue demonstrates, our theories of consciousness will not always align with our intuitions and we should be prepared for that, too.